Mitar's Point

science, technology, nature and (open) society.

Contact

Cookie consent fiasco

In May 2011 a EU directive was adopted with the goal of empowering web users with control over their exposure to cookies. The main issue is that 3rd party cookies allow users to be tracked across websites. The issue is that websites are often a mash-up of content coming from various services, each providing their own set of cookies. A service (a 3rd party) can thus track users across all websites using it.

In Slovenia I have participated in the process of adopting this directive into a local law which come into the effect in 2013. During this process I believed that the goal is good, and the law is reasonable. I thought that it handles technology well and with understanding, defining cookies broadly enough to be applicable to various tracking techniques and not just literally only cookies.

Maybe because of my participation and hearing all the arguments and perspectives I had a biased view, because once the law got into the effect a public outcry followed. At approximately the same time it got into the effect also in other EU countries which just reinforced public reception. Developers did not like that they had to do extra work and web frameworks they were using were not really helping them. It was unclear who will pay for that, especially because those changes were not planned and budgeted, especially for sites already made. To my surprise even developers who are otherwise outspoken about users’ privacy disliked the requirement of asking users for consent about cookies.

As a consequence, developers did not try at all to imagine how to address the spirit of the law and allow users to minimize their tracking around the web, but searched for a way to satisfy the letter of the law with the least amount of effort. Plugins have been developed which made it easy to turn site into a “compliant” site by showing users a banner where they were informed about cookies. Developers used them and move on.

Looking now back we can observe multiple issues with the whole process. First, different EU countries adopted the directive differently, but that was not really part of the public discourse, nor big international websites really payed much attention to it. This meant that if you read international information about the cookie requirements you got different information than if you would really read a local law itself. Even local news organizations got confused about it, sourcing information from their international partners. If you used a plugin developed by someone in a different country you might got a plugin which did not really made your site compliant. But because everyone wanted to do the least effort and least amount of work required by users, soon everyone converged to use the least demanding solutions.

For example, in Slovenia we required that users have to opt-in. It is not enough to just display a banner saying that by continuing using the website you agree with cookies. User had to click on a button to confirm. Some other countries focused more only on educating users about cookies and informing them that the website is using them, but not requiring them to do any action about it.

If you do provide a banner requesting from user to confirm, the question is what happens if they do not. Most developers I have seen decided to simply prevent user from using the website by redirecting them away. Or sometimes they redirected you back to the same website, displaying a banner again, forcing you to stay in this loop.

This made users learn that they should not really care what cookies are or whether they like them or not, but that they simply have to confirm the banner to be able to use the website at all. Developers managed to get users to confirm, but of course users were not really empowered in any way. Developers themselves understood that such banners do not really do anything meaningful. And this made part of a negative cycle which further diminished the perception of the law, and why would anyone spend time working on a good solution for a bad law?

Moreover, users became habituated to this banner and that they just have to confirm it and this is it. Even if a website would allow operation without cookies, users learned from other websites that this is not really an option to even try.

Furthermore, most banners are simply claiming that those cookies are required for site operation. But this is simply not true. Most 3rd party cookies are not. When using web with disabled 3rd party cookies as an experiment I noticed an issue only with commenting platform Disqus: I had to make an exception to be able to login to comment. But cookies for website analytics is definitely not needed from the perspective of the user.

It is interesting to note that in this case developers’ perception of the law guided their response which was then coded into the code and became interpretation of that same law, effectively became the law. The normative technology became the law. While original intent of the law was slightly different, at least how it was discussed during the process of adopting the EU directive, the code implementing it became the real law. Became what users see what the law is, and what other public see how reasonable and useful the law is. And because it is clear that banners are not really useful, the law itself is perceived as such as well.

In big international companies it seems that dealing with this regulatory change was done mostly by lawyers who are not really in a position to imagine technically changes needed to their website stack to innovate in a way which empower users and at the same time satisfy regulatory requirements. The easiest thing is to come up with a text to put on a banner and request from developers to display this banner to users.

The issue underlying this law is of course also the issue of enforcement. How to really enforce such requirements when web is global? If different EU countries have different requirements, how can a website know what to do for a particular user? Even before user really interacted in any meaningful way with the website. The website can use their IP to try to guess users’ geographical location, but this is not always precise. Who is liable when they make a mistake?

Moreover, having multiple versions for multiple countries is hard to develop and maintain. So the question posses itself: should websites implement the strictest requirements and thus satisfy everyone? But what if authors of a website believe that this degrades users’ experience of the website. Then we want to minimize the number of users who have to experience this degraded version of the website.

But it is really so hard to address legal requirements in a way which empowers users? When we were debating the law before it passed it was straightforward to us how it should work. Users should not get any 3rd party cookies by default and then only when they would request some feature of a website which requires them, they would be informed that cookies are needed for this particular feature and to proceed with loading/enabling it. This can work great for Facebook like and share buttons, YouTube and Google Maps embeds and many others. But it cannot work well for ads and analytics. Which is probably exactly those which the law wanted to protect against.

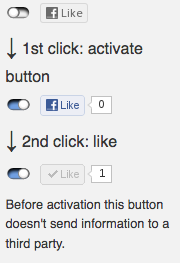

Social Share Privacy is an example of a plugin which behaves in this way. It uses a two-click approach, where the first click loads the 3rd party content and the second click then interacts with that content. It is a great and simple idea, which does not drastically worsens user experience, while at the same time empowers users.

Sadly, I have not seen other web frameworks or plugins providing such feature out of the box. If this would be something which would just work it would be much easier to get adoption. Similarly to how Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) protection became widely used once web frameworks provided it automatically. Then even developers would not see legal requirements as unreasonable. But privacy is not yet seen as important as security itself.

Existing web frameworks even use cookies in an anti-pattern in the respect to cookie laws, setting them immediately when user visits a website, and not when user requests a feature. For example, session cookie is automatically set, even if a website does not even use sessions or even if user has not yet logged in.

In some way it is thus understandable that developers have chosen an easier path. Law tried to force this change in an architecture of web applications but it did not happen. Maybe this effort was not coordinated enough and core developers of web applications did not feel enough personal motivation to coordinate better. So what could be a better way?

Maybe instead of requiring websites to provide such protection for users, law could first require it from web frameworks and service providers. Similar to how YouTube provides a nocookie version of its service. Maybe government could simply develop plugins for popular web frameworks. All that so that when later on developers are required to change websites, tools and services are ready.

Or was it a problem that the law allowed for multiple ways to ask for users’ consent. So developers chose the easiest one. Or is issue that in general developers are wary of Internet being regulated and was this a form of a protest as well? Would it be better if this would be done through a standardization body with many stakeholders? Including browser vendors. For example, the law has provisions for users to configure their browsers to inform websites about their cookie preferences. But no browser really provides such feature, and there is no standard yet to inform the website about cookie preferences. And it is unclear if anyone from the government even worked with browser vendors to implement something like this.