Mitar's Point

science, technology, nature and (open) society.

Contact

PeerDoc – Scaling real-time text editing

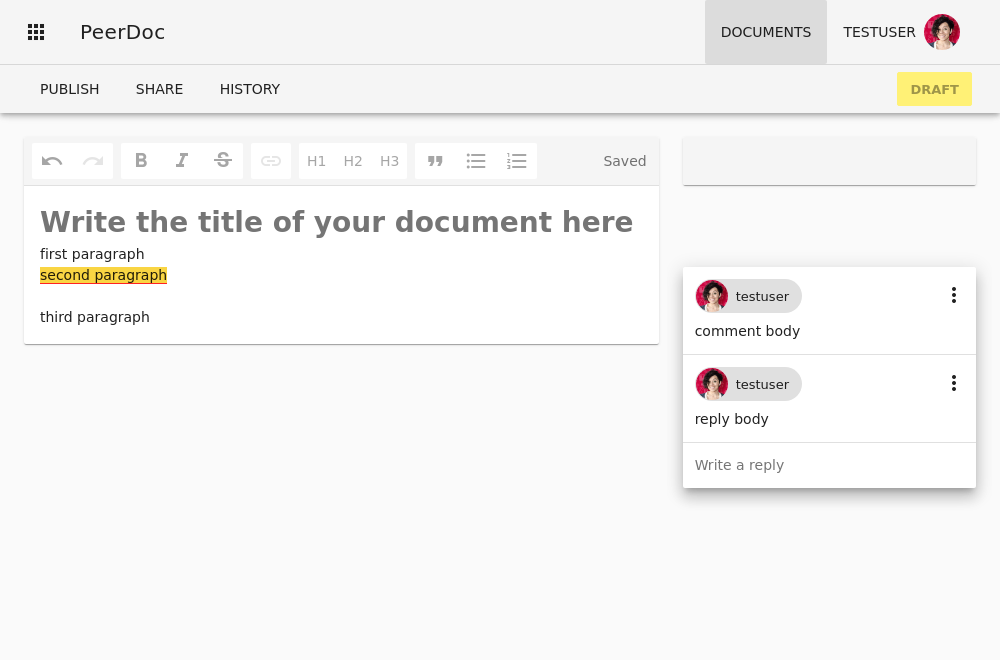

PeerDoc is a collaborative real-time rich-text editor with undo/redo, cursor tracking, inline comments, permissions/sharing control over documents, a change history. Things you would expect from a modern collaborative editor on the web.

But the main difference is that it combines two types of collaboration:

- real-time collaboration between collaborators on the draft of the document (push-based collaboration)

- fork and merge request style of collaboration with others, allowing collaboration to scale beyond a small group of collaborators (pull-based collaboration)

Push-based and pull-based collaboration

Push-based collaboration is collaboration where a change can be made directly (pushed). Google Docs and Wikipedia (and wikis in general), for example, work this way by default. If the change is deemed problematic by others, it can be reverted or further changes can be made to fix the problems.

Pull-based collaboration instead works by offering a change that must be approved before it is integrated (pulled). GitHub has popularized this model through its pull-requests (which GitLab calls merge-requests because integrating a change is called merging).

Both types of collaboration are widely used. Both offer some advantages and disadvantages. Push-based collaboration:

- Works best with a small group of collaborators (Google Docs limits collaborators to 100) who generally trust each other (Wikipedia needs editors who patrol recent changes to detect vandalism).

- It has less procedural overhead and is generally easier for a novice to understand and do.

- When done in real-time, potential conflicts (due to changes to the same section of the document) can be resolved more easily and quickly, often without having to coordinate the resolution at all.

- Each individual change is made by one user and there is no collaboration on the change itself. This can be less friendly to novice collaborators, who might prefer to have some help with their change. If their change is then further changed or even reverted, they may feel hurt.

Pull-based collaboration:

- Can scale up to many collaborators who can independently offer changes.

- Often, changes can be made, discussed, and iterated upon by collaborators, before they are integrated.

- Each change requires a review process before it is integrated (or rejected), which can become a bottleneck. This process must be learned by novice collaborators before they can contribute.

- Multiple independent changes may be made to the same section of the document and resolving conflicts is difficult to coordinate (since each change is usually part of a separate review process) and lengthy (can be repetitive).

- Collaborators need only trust those reviewing and approving the changes.

- There is usually a time and place to discuss the changes next to the changes themselves. These discussions can remain available for future reference.

Combining push- and pull-based collaboration

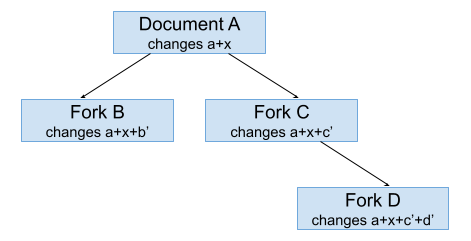

PeerDoc supports real-time editing for those who have permission to edit the document directly (given to them by the initial editor of the document). Others (if they have permission to see the document) can fork the document and edit the fork (the user who made the fork can also grant permission to other users to edit the fork). Later, an editor of the fork can suggest that all changes from the fork be merged back into the parent document. If an editor of the parent document approves, the merge is performed. A fork itself can also be further forked. This can soon lead to a tree of documents like this:

PeerDoc uses the great ProseMirror library for its editor, which already includes features for real-time collaboration. For a single document this works great, but making things work across a tree of documents requires a precise cross-document sharing of changes.

When a change x in Document A is made, it is made after all existing changes a:

Change x then has to propagate to Fork B and Fork C, integrating with other additional changes already there, changes b and changes c, respectively. This is done by rebasing those additional changes on top of changes from Document A. So all changes from Document A are always the oldest in the history, with forks adding changes on top of that history. Rebasing changes b on top of change x makes changes b’, and rebasing changes c on top of change x makes changes c’. After rebasing, changes b’ and changes c’ follow after changes a and change x.

Integrating changes from Document A into Fork C changes Fork C. Because of that, those changes (change x and changes c’) have to propagate in turn to Fork D. This is where rebasing becomes more complicated. Rebasing requires branches to have a shared base, but changes d have base a + c while to-be-rebased changes d’ have base a + x + c’. To get to a shared base we start with a + c + d and then invert (undo) changes c and changes d and add them to get a + c + d + (-d) + (-c). Then we add new change x from Document A to get a + c + d + (-d) + (-c) + x. With that we rebase changes c into changes c’ (which should produce same c’ as we got for Fork C) and now we can rebase changes d into changes d’. This gives us a + c + d + (-d) + (-c) + x + c’ + d’. We now add changes d’ as rebased changes to a + x + c’ to get fork’s changes a + x + c’ + d’ and forget those temporary transformations we made.

Merging a fork into the parent document is easier. First, we have to make sure all parent changes are propagated to forks. Then, merging is simply adding additional changes to the parent document. For example, merging Fork B into Document A would mean that we add changes b’ to changes a + x, making Document A have the same content as Fork B (until another change to Document A). Merging changes Document A, so now we have to propagate changes b’ to other forks, i.e., Fork C (and in turn Fork D).

This explains what is happening on the server-side. Client-side also has to adapt to these changes. For example, an editor which has Fork D open and displayed it is showing changes a + c + d + y, where changes y are local changes the editor might have and have not yet been send to the server-side. When server-side propagates change x and then sends updated Fork D to the client-side, the editor has to update showing changes a + c + d + y to changes a + x + c’ + d’ + y’ while preserving any other editor state. PeerDoc does not yet implement this and just resets the editor.

Discussion

As you can see, cross-document sharing of changes can be very active. Changes can be small (e.g., the user adds an extra character to Document A in real-time, which then propagates to the forks) or large (e.g., the user merges a large set of changes b’ into Document A, which then propagate to the forks). All of this not only puts a burden on the server, but can also confuse users, since large chunks of content can be changed while they are editing the document. Moreover, the interaction with existing changes (e.g., the interaction of changes b’ with changes c’ after changes b’ have been merged into Document A and propagated to Fork B) can sometimes be surprising. All conflicts between changes to the same section of the document are resolved mechanically, without regard to how a human understands the content. When editing in real-time, this is fine because editors can usually observe and adjust to the results of conflict resolution in real-time (e.g., “Oh, I got pushed into a bulleted list by another user, let me get out before I type more.”). Furthermore, conflicts tend to be small anyway. However, when mechanically resolving conflicts for larger chunks of content, this can lead to surprises and require followup fixes.

When we think about collaboration, we also need to think about the process and the goal of collaboration. Who can edit and when, and in the context of PeerDoc, who can edit and when in real-time, and who can edit and when using forks and merges. One approach is to decide this based on trust between users, and edit in real-time if they have high trust, and edit through forks and merges if they do not. But if the collaboration is part of a wider community, we may need more control over when something can happen. For example, should any editor of the parent document really be able to approve the merge request, or should there be a process for that? After the merge, can the parent document editors continue to edit the document directly, possibly modifying the just merged (and community-approved) change?

PeerDoc supports being embedded inside another tool, which can then control the collaborative process more precisely. Moreover, it can operate in two different modes. In one mode, documents can be forked and merged at any time, and editors can still edit documents directly. In the other mode, documents can be marked as published and only then can they be forked and merged, but they can no longer be edited directly. The idea is that editors can directly edit the document only while it is not yet published (it is a draft). Then they publish the document and others can see the document, fork it, edit the fork in real-time, and then suggest changes that can be approved or rejected by the editors of the document.

When a fork is merged, it can no longer be edited and changes from the parent document are not propagated to it. It remains frozen and archived. If fork is not merged, it can be published instead. What this means for the community depends on the community, but it could mean that the fork editors want to make it visible to the community as an alternative to the parent document (rather than retracting the proposed changes).

Deployment

PeerDoc has been used by The Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil, to write their 5 years strategic plan allowing everyone at the university to collaborate and contribute. It has been used integrated with AppCivist which guided the community through multiple phases of participation.

Collaboration is not easy

PeerDoc does not have all the answers (yet) about how exactly to best use a combination of these two types of collaboration. Are forks created by working groups that meet and collaborate and then propose changes to the main document? How are the proposed changes approved? Does an editor of the parent document make a decision or is there some other decision-making process, e.g., voting? What happens if a change is not approved? Does the community vote to choose between the parent document and a fork? Or is the fork published as an alternative document? Or is it simply forgotten? Is PeerDoc used as-is, or is it integrated with another application that can help organize the community and coordinate the process? PeerDoc currently rebases all changes and maintains a linear history of all documents, but would a branched history without rebasing be better when trying to understand how documents came about? Can one effectively proceed in followup fixes of poorly resolved conflicts without having access to both versions (parent and fork) of the content prior to the merge, or is it sufficient to see only the (poorly) merged result? More experimentation is needed to answer these questions. Try it out and please report your experiences.